Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA) Compliance: The Definitive Guide for Businesses

The Telephone Consumer Protection Act is a law established by Congress in 1991 to protect consumers from unwanted phone calls, text messages, and voicemails. Congress delegated rulemaking to the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”) which developed the implementing regulations for the TCPA. At a high level, the TCPA prohibits:

Calls made using an automatic telephone dialing system (“ATDS”), artificial, or prerecorded voice messages (collectively, “Regulated Technology”) without obtaining prior express written consent, and

Telephone solicitation calls and text messages to residential numbers on the National Do-Not-Call registry.

TCPA General Requirements

Not all customer communication is created equal. From a business perspective, every touchpoint is an opportunity, but under the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA), the legal requirements for those touchpoints are drastically different. The law makes a sharp, critical distinction between "informational" and "telemarketing" messages, and mastering this difference is the first step in building a compliant—and ultimately more profitable—outreach strategy.

The TCPA defines a telemarketing message as any communication that encourages the "purchase or rental of, or investment in, property, goods, or services." If your call or text has a commercial purpose at its core, it's telemarketing. Everything else falls into the category of informational messages. This includes appointment reminders, shipping notifications, or fraud alerts. The line can sometimes blur—an informational message might have an ancillary commercial benefit—but the primary purpose dictates the message type. For a leader focused on growth, taking a conservative approach here is always the safest and most defensible strategy.

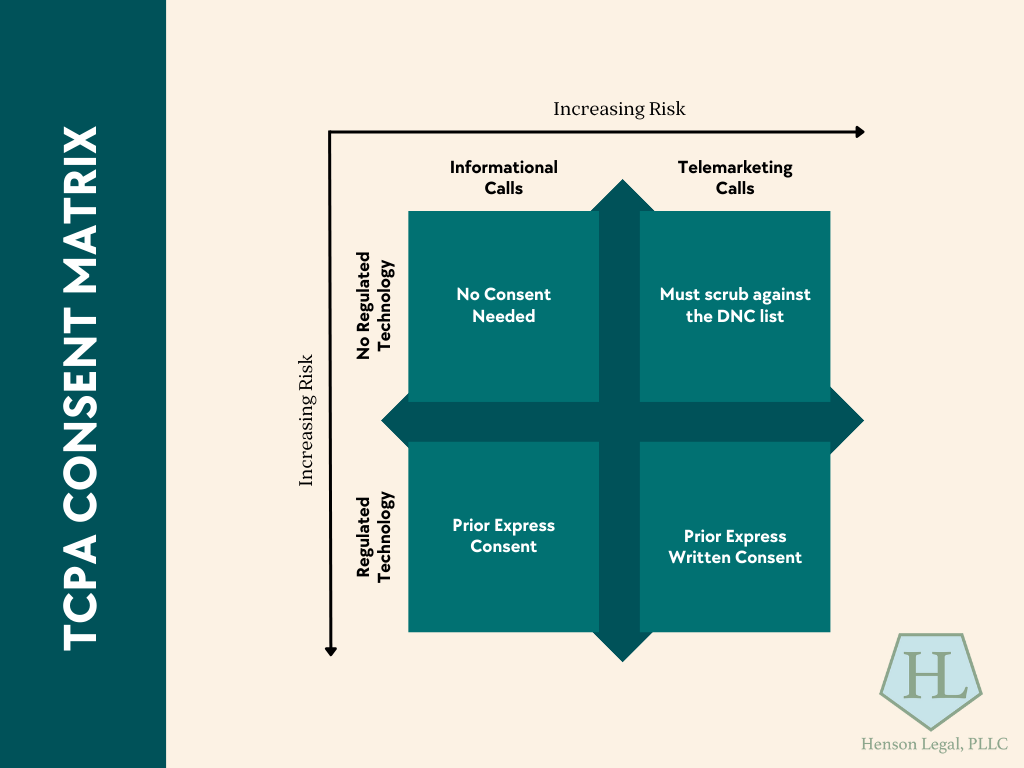

The Consent Matrix: Matching Your Method to Your Message

The type of consent you need depends entirely on two factors: the message type (informational vs. telemarketing) and the technology you use to send it. This isn't just a legal checklist; it's a business decision framework that directly connects your technology investment to your compliance risk.

The High Cost of Failure: Understanding TCPA Penalties

The TCPA has some of the most severe penalties in consumer protection law, primarily because it grants a private right of action. This means consumers can—and regularly do—sue companies directly, often in class-action lawsuits.

The financial risk can staggering:

Violations involving Regulated Technology (like autodialers or AI voice) carry minimum statutory damages of $500 per call or text.

Violations of the DNC registry rules allow for damages of up to $500 per call.

For any violation that a court deems to be knowing or willful, those damages can be tripled to $1,500 per call or text. When you multiply that by thousands—or millions—of messages in a class-action suit, it becomes a "bet-the-company" risk. This is precisely why a proactive, strategic approach to compliance is the only way to enable fearless growth.

Definition of an ATDS

The TCPA defines an automatic telephone dialing system as “any equipment which has the capacity to store or produce telephone numbers to be called using a random or sequential number generator and to dial such numbers.” Despite the regulation’s attempt to define what is an ATDS, this definition has been heavily litigated in efforts to determine what actually is an ATDS.

One such area of litigation was around the phrase “equipment which has the capacity”. This particular phrase has been interpreted by courts to look at what capability does the system have, not what was necessarily used by the caller. For example, “a system need not actually store, produce, or call randomly or sequentially generated telephone numbers, it need only the capacity to do it.”

The Supreme Court in Facebook v. Duiguid attempted to resolve this conflict “regarding whether an autodialer must have the capacity to generate random or sequential phone numbers.” The Court found Congress’s definition in the statute “requires that in all cases, whether storing or producing numbers to be called, the equipment must use a random or sequential number generator.” After interpreting the definition of ATDS, the Court held a “necessary feature of an autodialer…is the capacity to use a random or sequential number generator to either store or produce phone numbers to be called.”

However, in a footnote, the Court discussed a hypothetical that has added additional confusion to the issue. The Court stated:

Duguid argues that such a device would necessarily “produce” a number using the same generator technology, meaning “store or” in § 227(a)(1)(A) is superfluous. “It is no superfluity,” however, for Congress to include both functions in the autodialer definition so as to clarify the domain of prohibited devices. For instance, an autodialer might use a random number generator to determine the order in which to pick phone numbers from a preproduced list. It would then store those numbers to be dialed at a later time. In any event, even if the storing and producing functions often merge, Congress may have “employed a belt and suspenders approach” in writing the statute.

The Supreme Court case, specifically the footnote, did not end the litigation around ATDS definitions. In fact, other courts are still split on characteristics of an ATDS. One such court has stated “the weight of authority and Supreme Court’s dicta in Footnote 7 of Duguid…an autodialer that stores a list of telephone numbers using a random or sequential number generator to determine the dialing order is an ATDS under TCPA.”

Do-Not-Call Restrictions and Established Business Relationships

While the rules governing Regulated Technology often grab the headlines, a foundational layer of the TCPA that every business leader must master is the National Do-Not-Call (DNC) Registry. These regulations prohibit “telephone solicitations” to any residential number registered on the national DNC list. For any company conducting outreach, understanding what constitutes a "solicitation"—and more importantly, what doesn't—is the key to maximizing your market reach without incurring massive risk.

Understanding "Telephone Solicitations"

The TCPA’s DNC rules are built around a specific legal definition of a telephone solicitation, which is:

the initiation of a telephone call or message for the purpose of encouraging the purchase or rental of, or investment in, property, goods, or services, which is transmitted to a person, but such term does not include a call or message: (i) To any person with that person’s prior express invitation or permission; [OR] (ii) To any person with whom the caller has an established business relationship.

From a strategic perspective, the definition itself provides the blueprint for compliance. It carves out two powerful exceptions that every sales and marketing leader must understand: obtaining prior permission and leveraging an Established Business Relationship (EBR). While "prior express invitation or permission" is not clearly defined, the courts have generally interpreted it to mean the same as “prior express written consent”.

The Established Business Relationship (EBR): Your Key to Manual Outreach

The EBR can be one of the most valuable tools in your compliance arsenal. The TCPA defines an Established Business Relationship as:

A prior or existing relationship formed by a voluntary two-way communication between a person or entity and a residential subscriber with or without an exchange of consideration, on the basis of the purchase or transaction with the entity within the eighteen (18) months immediately preceding the date of the telephone call or on the basis of the subscriber’s inquiry or application regarding the products or services offered by the entity within the three (3) months immediately preceding the date of the call.

This definition creates two distinct types of EBRs, each with its own timeline:

Inquiry-Based EBR: This relationship is formed when a consumer reaches out to your business for information. It creates a three-month window during which you can legally make telemarketing calls to them, even if they are on the DNC list.

Transaction-Based EBR: This relationship is formed when a consumer makes a purchase or completes a transaction. It provides a much longer, eighteen-month window for follow-up marketing calls.

In certain situations, your company's affiliates may also be able to leverage an EBR, but only if a consumer "would reasonably expect them to be included." This "reasonable expectation" standard is a significant legal gray area and should be approached with a cautious, well-documented strategy including proper scripting and a holistic view of the customer experience.

The Critical Limitation: Why the EBR Doesn't Apply to Regulated Technology

This is the single most important strategic point for any high-growth company to understand. The EBR is an exception to the DNC rules only. It is not an exception to the separate TCPA rules governing Regulated Technology.

From a P&L perspective, a leader might see a valid EBR with a customer as a green light to contact them with the latest, most efficient AI-powered dialer. From a legal perspective, that is a direct path to a class-action lawsuit. If you use regulated technology for marketing, you must have prior express written consent, regardless of whether a valid EBR exists. Aligning your technology strategy with your compliance framework is absolutely essential for enabling fearless growth.

The Revocation of Consent Rule: A 2025 TCPA Update Leaders Must Understand

In 2025, the FCC fundamentally shifted the power dynamic for consent revocation, moving from a rigid, business-defined process to a flexible, consumer-friendly one. For any high-growth company, this isn't just a minor rule change; it is a clear mandate to re-engineer your customer communication and opt-out systems for speed, simplicity, and reasonableness.

The FCC's goal was to “make clear that revocation of consent can be made in any reasonable manner,” and the final rule puts the full weight of that standard on businesses.

The New Standard: Revocation in "Any Reasonable Manner"

The most significant change is the establishment of a new, broad standard for how consumers can opt out. Consumers can now “revoke prior express consent… in any reasonable manner that clearly expresses a desire not to receive further calls and texts.”

Crucially, the rule flips the legal burden of proof. It is now the caller’s responsibility to prove that a consumer's method of revocation was unreasonable under the circumstances. The requirement for callers to prove a negative (“the revocation was unreasonable because…”) is going to make standard processes to monitor revocation requests vitally important.

From a P&L perspective, fighting over what constitutes a "reasonable" opt-out is a losing battle that creates customer friction and immense legal risk. The competitive advantage lies in embracing this standard. Companies that make it easy for consumers to opt out through any common channel (email, phone, text) will build more trust and protect their brand reputation far more effectively than those who try to force consumers into a single, rigid opt-out path.

The Operational Mandate: From 30 Days to a 10-Day Turnaround

The rule dramatically shortens the compliance timeframe. Businesses must now honor do-not-call and consent revocation requests within a reasonable time, not to exceed ten business days of receipt. This is a significant reduction from the previous 30-day window.

For a tech-enabled, high-growth company, the goal should be near-instant, automated compliance. A 10-day manual process is a sign of operational inefficiency. Building a seamless, real-time opt-out system is not just about avoiding fines; it's about operational excellence. It prevents the costly and brand-damaging mistake of contacting an angry consumer who has already asked you to stop, which is a key part of enabling fearless and efficient growth.

The Revocation "Safe Harbors": Methods You Must Be Able to Process

To remove any ambiguity, the FCC pre-approved several methods as "per se reasonable," meaning they are automatically considered valid. Your systems must be able to process these flawlessly.

Using an automated, interactive voice or key-press mechanism during a call.

Replying to a text message with keywords like STOP, QUIT, END, REVOKE, OPT OUT, CANCEL, or UNSUBSCRIBE.

Using a website or telephone number that you have designated for processing opt-out requests.

The rule adds an important nuance for text messages: even if a consumer doesn't use the exact keywords, the reply must be treated as a valid revocation if a "reasonable person would understand those words to have conveyed a request to revoke consent."

Finally, the rule clarifies that businesses are limited to sending a single, one-time text message to confirm the consumer's opt-out request. Any further communication is a violation.

Mastering the TCPA requires a holistic understanding of its core components—the technology you use, the relationships you have, and the rights your customers hold. By building a strategy that respects the nuances around the use of Regulated Technology, the power of the EBR for manual outreach, and the simplicity of the new revocation rules, you do more than mitigate risk. You create a compliant, trustworthy, and efficient communication program that stands apart from the competition, turning your biggest legal challenge into your greatest asset for sustainable growth.